To medicate or not to medicate: the question clients ask me all the time.

One of the questions I am asked most often in my counselling work is whether I think a client I am working with should take anti-depressants. It comes up most weeks and for lots of reasons.

Medication is often the “go-to” or first response clients get when they visit a GP - afterall, doctors are trained to “treat” problems with medicine and/or surgery.

Medication is widely-available and is sometimes presented as a simple solution or a quick fix to a problem.

Medication is how we treat lots of problems in our lives: aches and pains; blood pressure issues; hay fever; diabetes and so on.

And, medication is the subject of much debate, discussion and downright controversy, which can often lead clients not knowing who to trust, who to listen to, and what to do.

When the question comes up, I always answer with a question: what do you think?

More often than not, the client already has “priors”: pre-existing views, based on their own experience, or the experience of others. Often this view is informed by their feelings about medication in general, big pharma, and their stance on things like vaccinations. Often too, clients bring their understandable worries that they will be changed by the tablets - it will alter their personality - and that they will become addicted and be stuck popping pills forever. They worry that the side effects - the source of much of the controversy - will be worse than the issue they are seeking help for in the first place.

I know these worries and fears, not just as a therapist, but because I held them too. I was one of those asking the questions. I took them to my doctor and my therapist. I ruminated on them for months. I sat crying in the office of a psychiatrist when he suggested - fairly forcefully - that I start taking an anti-depressant. I lived them - not just from a textbook but in my real life; in my world marred by depression and anxiety; in the middle of my breakdown and its after-effects.

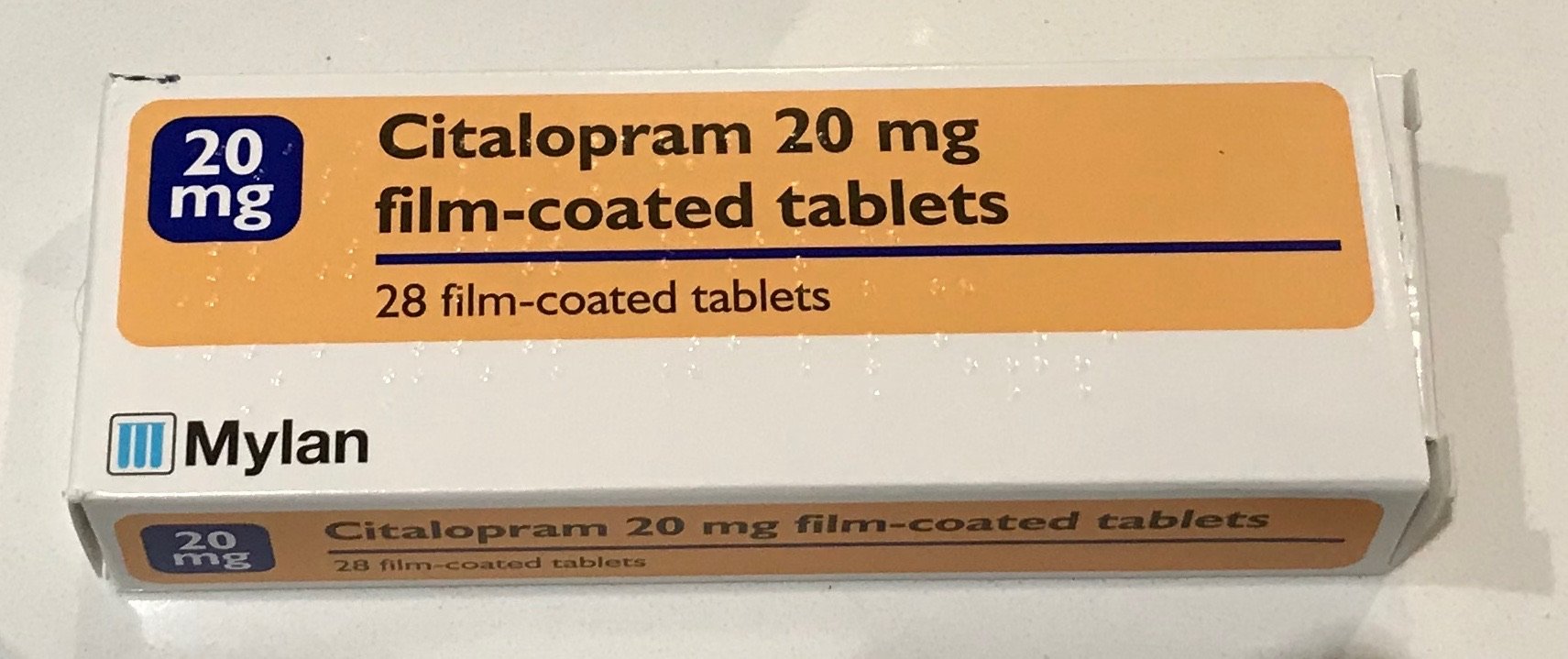

I am not a doctor or a pharmacist. I do not have prescribing powers. I have not studied the chemical make-up of these little tablets. But I can tell you about my experience - of my 19 months taking an anti-depressant (Citalopram) - and coming off an anti-depressant - and the experiences that clients share with me.

Let me talk about me first. My experience was positive. The side effects were there - I felt them but they were manageable. I know that is not the case for everyone and that some people’s experience of side effects can be horrendous. I know too that the information leaflets with the medications make this clear - and set out in some details the wide range of possible side-effects and what to do if we face them.

My side effects included some nausea and headaches (they didn’t last much more than a week or two); extra tiredness in the evenings (that was a fairly permanent state whilst taking the medication); some weight gain at first (lasting a month or two); some impact on my enjoyment of a wide range of activities, including those I used to get a lot of pleasure from, which was part physical (relating to fatigue - a common side effect) and part psychological (related to the main impact of the medication, which is emotional numbing most people experience - as least to some degree).

This emotional numbing means that as well as smoothing the rough edges of low mood and sadness, making negative things feel less negative, it had the same effect on positive or happy things. They didn’t feel as good or happy. This included the impact it had when Liverpool scored a last minute winner in a big game, which I greeted with a feeling of mild satisfaction not the unusual euphoria or joy.

This was the fundamentally tricky thing about the experience of medication. It smoothed out lows. Good news. But it also smoothed out highs. Not so good news.

On balance, I accepted these two effects because overall life was easier, more manageable and less stressful and anxiety-inducing. It is hard to pin down or describe in tangible detail - something clients say to me regularly - but life just felt more do-able and less difficult. The biggest benefit I experienced - and again I have clients who share with me their own similar experience - is that the medication frees up some space in their head - which is probably the effect of reduced anxiety and related low mood - to focus on other things. It gave me breathing space. Freedom. Space to think. Time to think.

In my personal experience, and the experience of many of my clients, the key thing that makes or breaks the experience of using medication, is what to do with this mental/emotional/psychological breathing space. Can we use the space in our heads to talk through some of our experiences and issues which is causing us the discomfort and/or distress? Can we take this new-found opportunity to focus on the resets we may need or want to make? Can we make whatever changes we may need to make this breathing space from negative stuff permanent?

This is what I did. The positive effect of the medication meant that I was able to use the time I wasn’t worrying or crying or just feeling that life was too hard, to make other changes which could out-last the medication. This where my jam jar came in - doing all the things - every day - that help me feel more content in the world, including giving up alcohol and taking up being kinder to myself and realising that I deserved to be treated as well as I treated others.

When I talk with clients about their decision to start on medication, I often find us having a similar conversation. We try to explore how we can complement the medication’s work on the symptoms - hopefully reducing day-to-day anxiety and low mood - by working on the underlining feelings; the root causes; the triggers; the experiences that have led to the anxiety and low mood in the first instance.

I know that many, many GPs - in line with NICE guidelines - talk to their patients about the importance of the combination of medication with talking therapies and/or other interventions which can help us work on our improving our mental health (including exercise, diet, sleep and more). But, I know too that some find they take the medication, feel a little better in the short term, and then plateaux and get stuck. Stuck with their feelings and stuck on the tablets.

That brings me to the process of coming off the medication when the time feels right. For me, I reached the point where the numbing of my feelings - which had been helpful - was now stopping me enjoying life enough to not want to continue with the tablets. But the key thing for me was that I had by that time made the other changes, done the talking work with my therapist, and managed the reset that I needed in my life, to try to go on without the help of the medication. That is of course just my story and everyone has their own experience and decisions to make about if and when to stop medication.

Whatever the timing of that decision, it is critical that coming off the medication is done in a managed, slow and sensible way - with the support and guidance of a doctor. Cold turkey is not helpful. Weaning or tapering off in quick time is not helpful. Cold turkey and/or quick weaning or tapering can be very dangerous. Although every journey and all decisions to take and then stop taking medication are individual, there is a universal truth: it must be done by following the guidance and advice of a doctor.

Every client I see is unique. Everyone brings their own histories, beliefs, experiences and personalities. Everyone’s needs are different and everyone’s therapy with me is tailored to them.

Everyone’s journey with medication should also therefore be unique and tailored to the needs of the person.

To medicate or not to medicate, that is the question I am asked. The answer - like everything in life - is that it depends. It depends on each of us. It is personal. It is about our own needs. Our own situation. Our own choice. It’s our life.

But, it must be done under the supervision and with the support of a doctor, who is qualified and trained to help us plot a course that meets with our overall health and medical needs.

We need information about our options. We need information about side effects. We need to be clear about our plan and - ideally - how we complement medication with other work that can help us. But, we also need to listen to the experts in medication: our doctors. They don’t always know what is best for our emotional needs and whether we should to take medication - but they do know how we should take them and how we should stop taking them.

To medicate or not to medicate is a decision for every individual - but “the how” to medicate and then not to medicate should not be done alone.